Case Study:

Chloe and Nikki: Improving language and engagement through embodied artistic learning

Site: Kangaroo Children’s Centre

Year level: Early Learning

Context

Chloe and Nikki are part of the early learning team at Kangaroo Children’s Centre, a site north of Adelaide that caters for Aboriginal children and their families. Having graduated the previous year, Chloe is new to teaching and to Kangaroo Children’s Centre. However, as an Aboriginal woman who grew up in the community, Chloe is a familiar face to the children and families that come to the site. Nikki, who is non-Indigenous, completed university in 2012 and after a couple of years working on the APY Lands [1]—an experience she relished—she accepted a permanent teaching role at Kangaroo Children’s Centre. She has since become the Director of the centre. During her university years, Nikki had learnt about the educational philosophies of the Reggio Emilia educational project. Then, as a result of Professor Carla Rinaldi’s tenure as ‘Thinker in Residence’ in Adelaide (2012-2013), Nikki’s commitment to the Reggio Emilia approach deepened. In 2019, Chloe and Nikki were further inspired when they participated in a study tour of Reggio Emilia, Italy, where they saw first-hand the educational philosophies put into practice.

Kangaroo Children’s Centre is located in an area that is currently experiencing significant economic issues due to the closure of local industries. Unemployment is nearly triple the South Australian average, and of the people who are employed, a relatively high proportion are in occupations that are not well paid. As a consequence, some families are facing socio-economic stress. The Aboriginal population in the region is more than double the state average, and many of the Aboriginal families who bring their children to Kangaroo Children’s Centre face a range of challenges in relation to finances, housing, health, social disadvantage and daily racism. In 2019, a total 50 children aged between three and five years were enrolled at the centre. Due to significant increases in demand, wait list times have soared over the past three years. Staffing includes the Director(Nikki), three teachers, two education care workers, an occupational therapist, and a speech pathologist. A range of services support the centre, including a Family Practitioner and a Community Development Co-Ordinator.

Although all the families at Kangaroo Children’s centre are of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander heritage, there is much diversity in terms of the Aboriginal Nations and language groups represented. These groups include Warlpiri, Anmatyerre, Arrernte, Luritja (NT); Wiradjuri (NSW); Banjima (WA); Kaurna, Narungga, Ngarrindjeri, Adnyamathanha, Anangu (Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara), Peramangk and Ngadjuri (SA). Most or the verbal children speak English or a variety of Aboriginal English as their first language. There are also two or three children who speak an Aboriginal language as their first language.

Staff at Kangaroo Children’s Centre manage a number of complexities which challenge them to grow as educators. Many children have experienced significant trauma in their lives, so trauma-informed practices are used to support children’s sense of safety and their self-regulation. The development of positive relationships with staff is considered fundamental to the well-being of the children and their families. More than half of the children receive speech and language support. Physically, the centre has relatively small indoor and outdoor spaces, which the staff utilise as far as possible. During the year, major site upgrades were undertaken and the children and their educators had to temporarily relocate to the adjacent child-care centre for several months. This relocation added to the challenges faced by staff, children and families.

[1] APY: Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara. A local government area in remote north-western South Australia owned and governed by the Aboriginal peoples of the region.

The pedagogical challenge

Across this range of complexities, Chloe and Nikki decided to focus on the challenge of children’s engagement, especially in relation to orality and literacy. At the end of Term 2, based on staff observations in conjunction with the use of the Reflect Respect Relate (RRR) educator resource, Chloe and Nikki identified that children’s meaningful engagement levels were low, due to a number of factors including trauma, challenging behaviours and Global Developmental Delay. In addition, many parents had concerns about their children’s oral language skills, and screening tools used to monitor children’s speech and language development supported these concerns. Parents were also keen to see more Aboriginal language and cultural activities embedded in the daily routine. Chloe and Nikki designed a research question that integrated these challenges.

The action research question

How do Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and the Reggio Emilia approach improve literacy/orality skills and engagement levels of children through embodied artistic learning?

Links to Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

- Connected to the lives of learners

- Performing learning and multimodal literacies

- Recognition of culture as asset

Links to the Reggio Emilia approach

- 100 Languages

- Participation

- Pedagogy of listening

- Environment, space and relations

What Chloe and Nikki did

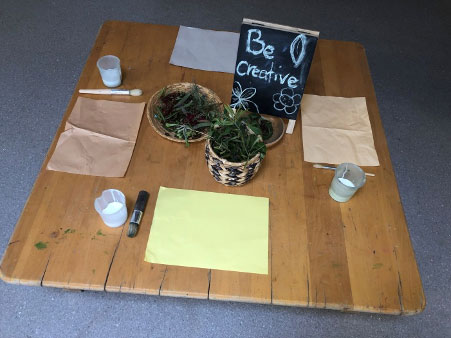

Following the CRP principle that learning should be strongly connected to children’s life-worlds, Chloe and Nikki decided to focus on Aboriginal Dreaming stories to engage the children in more meaningful learning experiences. Previously, books based on Dreaming stories had been on display in the centre, including ‘How the birds got their colours’ (2011), ‘Tiddalik the frog’ (2004) and ‘Thukeri: A Ngarrindjeri Dreaming story’ (1996). Children could access these books if they chose to do so, but there had been few hands-on activities based on the stories to foster deeper engagement, and some staff did not feel confident with the genre.

In order to support greater engagement, Chloe and Nikki collected a range of resources to use as ‘props’ in hands-on activities relating to the Dreaming stories. They took the children outside to the centre’s bush garden to collect bark, sticks and other items from the natural environment that could be used by the children to ‘act out’ the stories. They also sourced models and toys relating to the story themes. With a pack of these props for each Dreaming story book, they sat down either indoors and outdoors with groups of children to read and re-enact the stories together.

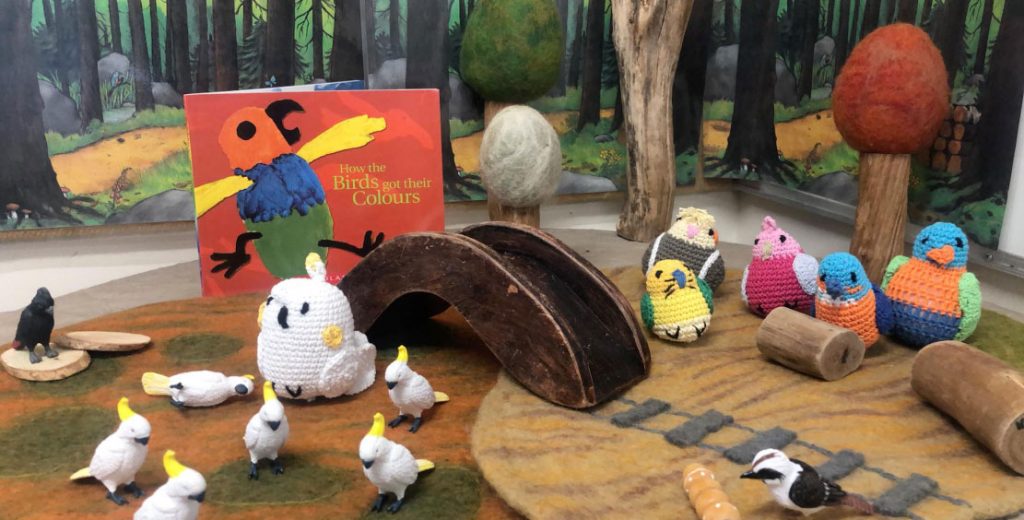

Chloe and Nikki also made other intentional changes to the learning environment. They sought input from the families to identify useful Nunga[1] words, primarily from Kaurna, Pitjantjatjara, Narungga, Ngarrindjeri and Aboriginal English, to introduce into the daily routine. They used the upgrade of the facilities to alter the learning environment, with an emphasis on a more soothing atmosphere (such as natural items and nature play, neutral colours, calming music and scent diffusers). They also upskilled staff and kept them informed of their developing understandings of Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and the Reggio Emilia approach.

The range of data they collected included:

- Phonological awareness evaluations

- Levels of questioning

- RRR Wellbeing scales

- RRR Engagement levels

- Photos

- Videos

- Critical reflections of research leads and other staff

- Parent questionnaire and verbal yarns

- Child thoughts

- Child observations

[1] Nunga: A collective term for South Australian Aboriginal peoples

Outcomes for the children

Since implementing changes to the learning environment, staff at Kangaroo Children’s Centre have noticed:

- Children show a greater interest in Dreaming stories and books when they were accompanied with props to support the story.

- Children are able to re-tell and recall events of the stories and implement this in different contexts throughout play.

- Children’s language/orality has increased. They are able to maintain reciprocal shared conversations at a deeper level.

- Children are more responsive when staff use Nunga language on a daily basis .

- Children’s wellbeing increases when they are more engaged

- Children have a stronger sense of belonging and identity in groups and are forming relationships with their peers.

- Pre-verbal children are communicating at a greater level by interacting with the Dreaming story packs. They are expanding their relationships with peers.

Case study children

The outcomes for two children were documented more closely by Chloe and Nikki:

| Kane (boy, aged 5) |

Before

|

|

After

|

| Kasey (girl, aged 5) |

Before

|

|

After

|

Challenges

- Major site renovations requiring children and staff to relocate to the adjacent childcare centre impacted on the research plans

- Staffing changes

- Finding time and opportunity to engage staff all at once due to work patterns; higher level of staff engagement will share involvement and accountability

- Developing staff confidence in telling Dreaming stories

- The research question became much larger than originally planned. The original focus was on literacy and then, after Chloe and Nikki’s study tour to Reggio Emilia, Italy, it expanded into the Reggio-inspired environment. They realise they need to stick to one targeted outcome and keep on track with the research question

- Director duties on top of the project in a very complex site

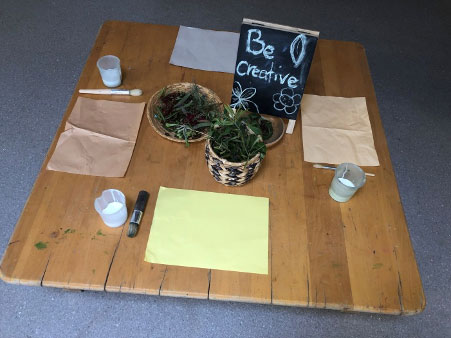

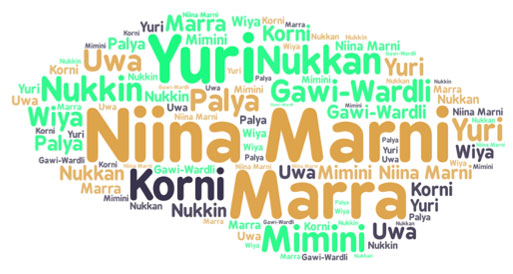

Dreaming story props:

How the birds got their colours

Tiddalik the frog

Thukeri

Conclusions

From their research, Chloe and Nikki witnessed the positive outcomes that Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and the Reggio Emilia approach can have on children’s learning and also on teacher practices. They realise that many of their site practices already had links to these two educational philosophies; it was a matter of noticing, acknowledging and expanding on these links. For example, staff are now more conscious of the pedagogy of listening and the importance of recognising all forms of communication (the 100 languages of children). In terms of the action research, they believe that timelines and organisation are key to success but they also realise that it is OK if things don’t go entirely to plan.

In future, Chloe and Nikki intend to encourage families and community to be more involved in site activities, for example by inviting them to tell the Dreaming stories. They want to incorporate more Nunga words, such as the names of the animals in Dreaming stories, and ensure that Aboriginal languages and cultures are entwined throughout all learning experiences. From a literacy perspective, they plan to introduce syllable play to the learning activities. They intend to work towards whole-of-site staff involvement as they adopt an ‘educator as researcher outlook’ to investigate any pedagogical challenges that arise. And finally, they want to ‘Do more: IT WORKS!’

References

Faundez, A (2004 ) Tiddalik the frog. QED Publishing, London.

Albert, M & Lofts, P (2011) How the birds got their colours. Scholastic Australia, Gosford, NSW.

DECS (1996) Thukeri: A Ngarrindjeri Dreaming story. Department of Education and Children’s Services, South Australia.

Nunga vocabulary:

Learning enviroment