- Gloria Ladson-Billings[3] provides one of the many alternative versions of culturally responsive pedagogy and her work is primarily for improving learning outcomes for African-American children. Her version of culturally responsive pedagogy ‘rests on three criteria or propositions: (a) Students must experience academic success; (b) students must develop and/or maintain cultural competence; and (c) students must develop a critical consciousness through which they challenge the status quo of the current social order’.

- For Villegas and Lucas[4] the problem is the increasing cultural and linguistic diversity of classrooms that requires attention and they argue for a theory of the culturally responsive teacher that has these six characteristics: (a) is socioculturally conscious, (b) has affirming views of students from diverse backgrounds, (c) is capable of bringing about educational change that will make schools more responsive to all students; (d) is capable of promoting learners’ knowledge construction; (e) knows about the lives of his or her students; and (f) uses his or her knowledge about students’ lives to design instruction that builds on what they already know while stretching them beyond the familiar.[5]

- Kaupapa Maori researchers and educators have developed their own version of a Culturally Responsive Pedagogy of Relations. To quote from their most extensive definition that has these elements: power is shared, culture counts, learning is interactive and dialogic, connectedness is fundamental to relations, and there is a common vision of excellence for Māori in education (Bishop et al, 2007 p.15).[6]

- Our conceptual framework draws upon the Eight Alaskan Culturally Responsive Teacher Standards to guide our research process and inform our theoretical work. Alaskan Culturally Responsive Teacher Pedagogies include: teaching philosophy encompassing multiple worldviews; 2. learning, theory and practice knowing how students learn; 3. teaching for diversity; 4. content related to local community; 5. instruction and assessment building on student’s cultures; 6. learning environment utilising local sites; 7. family and community involvement as partners; and 8. professional development.[7]

- Castagno & Brayboy[8] (2008) argue that culturally responsive educators engage the cultural strengths of students and engage constantly with their families and communities in order to create and facilitate effective conditions for learning. They see student diversity in terms of student strengths; they orient to it as presenting opportunities for enhancing learning rather than as challenges and/or deficits of the student or particular community.

- We also borrow from Chris Sarra’s[9] Stronger Smarter philosophy which encapsulates the following conditions for improving educational outcomes for Indigenous students:

- Requires a focus on positive engagement (rather than being punitive)

- Demand for high expectations for all Indigenous students

- Indigenous students need opportunities to develop a positive sense of their cultural identity

- Educators to work in partnership with community

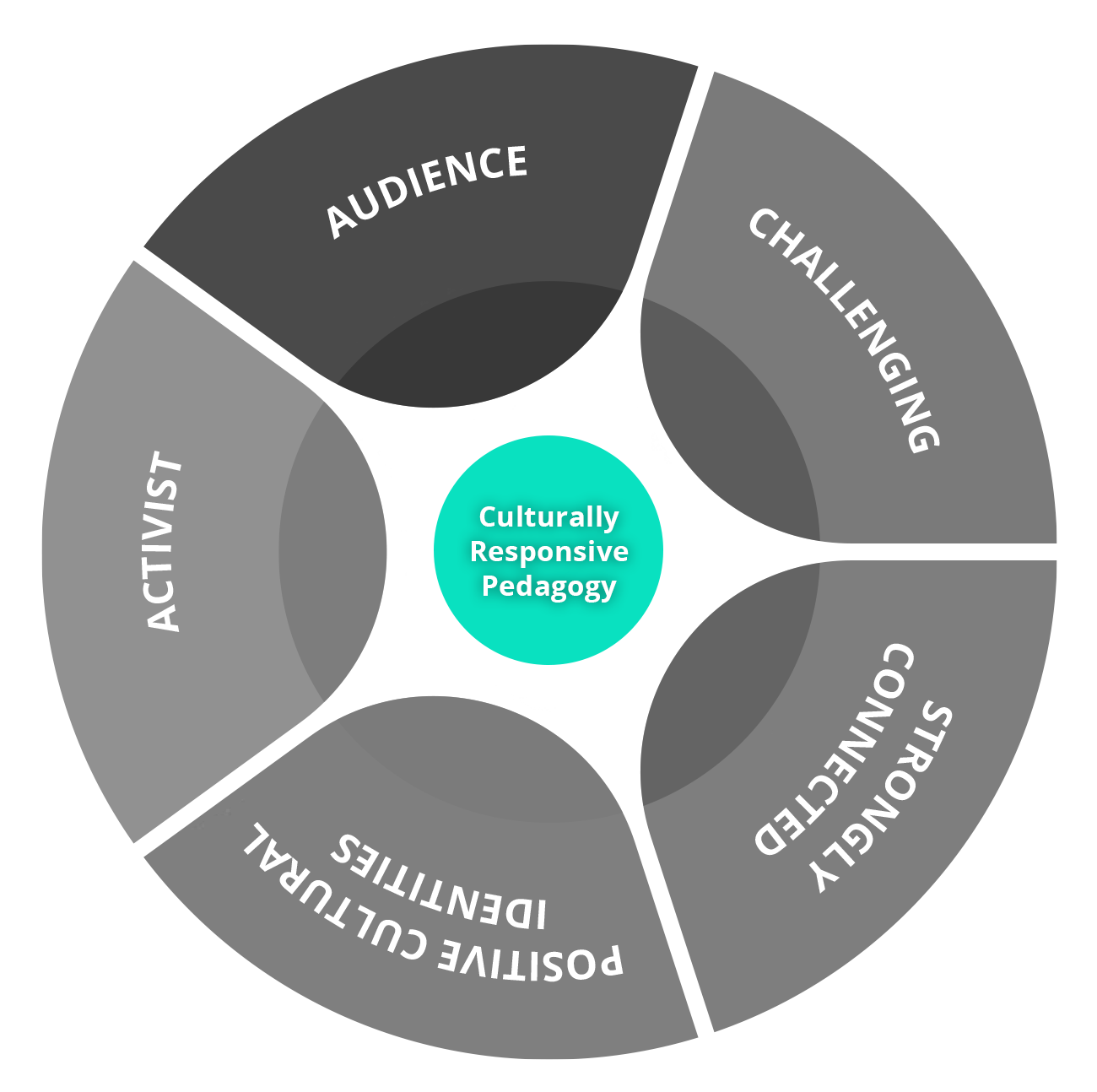

For pragmatic reasons, we did decide early in this project to foreground a very small number of themes, that was asserted strongly across the Pacific Rim culturally responsive pedagogy archive. We have working with these five themes or provocations to thought, that we think captures what a culturally responsive pedagogy needs to do: (1) provide high intellectual challenge; (2) connect strongly to students’ lifeworlds; (3) ensure that all students feel positive about their own cultural identity in classrooms; (4) demand that students perform their learning for an audience and open up options for using digital technologies [multimodal literacies] for demonstrating their learning for assessment learning; and, (5) taking up an activist orientation. For our framework, any claims to a culturally responsive pedagogy requires thinking about these five as a constellation of practices, operating as an interacting set.

[1] See Morrison, A., Rigney, I-L., Hattam, R. & Diplock, A. (2019) Toward an Australian culturally responsive pedagogy: A narrative review of the literature. University of South Australia. https://apo.org.au/node/262951, …p.13 for a list of synonyms and related references.

[2] Paris, D. (2012) Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice, Educational Researcher, 41(3): 93–97.

[3] Ladson-Billings, G. (1995) Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3): 465–491. See page 160 for quote above.

[4] Villegas, A. M. & Lucas, T. (2002a) Educating culturally responsive teachers: A coherent approach. Albany: SUNY Press; Villegas, A. M. & Lucas, T. (2002b) Preparing Culturally Responsive Teachers: Rethinking the Curriculum Journal of Teacher Education 2002; 53(1): 20-32; Villegas, A., & Lucas, T. (2007). The culturally responsive teacher. Educational Leadership, 64(6): 28–33.

[5] Ibid, 2002a, p.21.

[6] Bishop, R. Berryman, M. Cavanagh T. & Teddy, L. (2007) Te Kōtahitanga Phase 3: Whānaungatanga: Establishing a Culturally Responsive Pedagogy of Relations in Mainstream Secondary School Classrooms. The Ministry of Education, New Zealand.

[7] Assembly of Alaska Native Educators (1999) Guidelines for Preparing Culturally Responsive Teachers for Alaska’s Schools. Anchorage, Alaska.

[8] Castagno, A. & Brayboy, B. (2008) Culturally Responsive Schooling for Indigenous Youth. A Review of the Literature. Review of Educational Research. 78(4): 941–993.

[9] Sarra, C. (2007) Young, black and deadly: Strategies for improving outcomes for Indigenous students, in M. Keeffe & S. Carrington (eds), Schools and diversity (2nd edn), Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Education Australia, pp. 74–89.

[1] See Morrison, A., Rigney, I-L., Hattam, R. & Diplock, A. (2019) Toward an Australian culturally responsive pedagogy: A narrative review of the literature. University of South Australia. https://apo.org.au/node/262951, …p.13 for a list of synonyms and related references.

[2] Paris, D. (2012) Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice, Educational Researcher, 41(3): 93–97.

[3] Ladson-Billings, G. (1995) Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3): 465–491. See page 160 for quote above.

[4] Villegas, A. M. & Lucas, T. (2002a) Educating culturally responsive teachers: A coherent approach. Albany: SUNY Press; Villegas, A. M. & Lucas, T. (2002b) Preparing Culturally Responsive Teachers: Rethinking the Curriculum Journal of Teacher Education 2002; 53(1): 20-32; Villegas, A., & Lucas, T. (2007). The culturally responsive teacher. Educational Leadership, 64(6): 28–33.

[5] Ibid, 2002a, p.21.

[6] Bishop, R. Berryman, M. Cavanagh T. & Teddy, L. (2007) Te Kōtahitanga Phase 3: Whānaungatanga: Establishing a Culturally Responsive Pedagogy of Relations in Mainstream Secondary School Classrooms. The Ministry of Education, New Zealand.

[7] Assembly of Alaska Native Educators (1999) Guidelines for Preparing Culturally Responsive Teachers for Alaska’s Schools. Anchorage, Alaska.

[8] Castagno, A. & Brayboy, B. (2008) Culturally Responsive Schooling for Indigenous Youth. A Review of the Literature. Review of Educational Research. 78(4): 941–993.

[9] Sarra, C. (2007) Young, black and deadly: Strategies for improving outcomes for Indigenous students, in M. Keeffe & S. Carrington (eds), Schools and diversity (2nd edn), Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Education Australia, pp. 74–89.