Case Study:

Rachel’s History and Essential English units

Teacher: Rachel Wood

School: Roma Mitchell Secondary College

Context

Year 10 History

The pedagogical challenge

Students were studying a previously developed unit of work on Aboriginal history, but the content was repetitive and tended to focus on events in the distant past to the exclusion of relevant contemporary issues. Some of the content was tokenistic and did not explore issues in depth. While students learnt about and could recall events, they did not engage with the themes at an emotional level. In effect, the students had become desensitised to the content because Aboriginal history been presented repetitively and unimaginately each year as they progressed through their schooling. As one student remarked, ‘We’ve done this before’.

At the same time, a new course needed tobe created that could be extended over a semester, and that related to the previous history unit of Rights and Freedoms. These converging concenrs prompted Rachel to devlop a new unit of work on Aboriginal history grounded in her developing understanding of culturally responsive pedagogy.

Theoretical Basis

Rachel was drawn to Gloria Ladson-Billings’ (1995) model of culturally relevant pedagogy. Although this model was focused on improving learning outcomes for African-American children, the principles were equally applicable to other student cohorts. Billings’ version of CRP rests on three criteria or propositions:

- Students must experience academic success

- Students must develop and/or maintain cultural competence

- Students must develop a critical consciousness through which they challenge the status quo of the current social order.

Links to the ‘five key ideas’

- Offer high intellectual challenge

- Raise socio-political consciousness

The action research question

How can the discussion of sensitive cultural issues through meaningful open-ended questioning improve students’ emotional engagement and/or empathy?

Doing the action research

A new Year 10 History unit was created to focus on the repatriation of Indigenous artefacts and remains with the purpose of engaging students with a contemporary issue they would have heard little about.

The unit ran for 10 weeks over the course of two terms. There were two summative tasks―the first a source analysis and the second a combination of a press release and letter. Meaningful questioning was incorporated into explicit teaching, class discussions and the assessment task sheets.

Development of the unit involved all Year 10 History teachers, ASETOs[1], and the Aboriginal Education Coordinator, Alistair, who was also participating in the CRP project with Rachel. The unit was delivered by all Year 10 History teachers, however only Rachel’s class was the focus of the action research. Rachel was supported by Alistair, who was also her line manager.

The unit began with frontloading, showing an episode of the ABC series You Can’t Ask That, where a group of Indigenous Australians were asked ‘taboo’ questions. Students then answered a selection of the same questions about their own cultural identity. This was an individual activity in order to maintain privacy. Some students did not feel part of a ‘culture’, but made some connections between themselves and family or religious groups. Many Anglo Australian students felt ‘cultureless’―something the staff had anticipated may occur.

Students engaged with news articles about the repatriation of Indigenous artefacts and remains, and were asked challenging questions such as ‘Should these artefacts be kept in museums if it gives the public the opportunity to learn more about Indigenous culture?’ Many of the questions were contentious, and students were reluctant to share their ideas at first, possibly out of fear of offending others. This warranted group discussion, where students could share their thoughts with a smaller peer group. Group discussion allowed students to hear multiple perspectives, encouraged students to look at issues from the point-of-view of multiple stakeholders, built students’ confidence in asking questions but also in answering questions asked by their peers (and not always being teacher-directed).

In terms of pedagogy, when directing questions to the whole class it was important to allow waiting time to enable students to give genuine responses, rather than saying what they thought the teacher wanted to hear. Sometimes Rachel waited 30 seconds or so, and students slowly got used to being given more time to respond.

For their first task, students watched and read a variety of sources about repatriation, then completed a source analysis of one ABC News article, identifying the message, audience, agenda, author and tone. Students who were not consistent in completing or submitting written work were given the opportunity to verbalise their learning, which could then be assessed.

For their second assessment task, students were introduced to two text genres: letter and press release. Students were confident with the letter format, but none had previously seen a press release. The task required students to write two texts:

- A letter written from the perspective ofa descendent of an Indigenous person whose body is held in a museum in England, arguing why the remains should be returned to Australia.

- A museum press release justifying why the institution had held on to the body for so long.

This task required students to confront some ethical dilemmas, and to consider the different perspectives of the stakeholders. This created some discomfort, and many students agreed that the museum should return the body. However the task also encouraged them to see history as not necessarily a dichotomy of good versus evil, but involving different perspectives which change over time, and involving people who at different points in history believed they were right.

Students also participated in the role play Aboriginal history in South Australia since 1800 facilitated by the site’s two ASETOs. The role play is a visual and interactive representation of historical events in SA after colonisation and how they impacted on Aboriginal peoples. Students created maps of the land based on a description, and this land and its occupants were moved forcibly while a timeline was read aloud. Confusion was the initial reaction, which was the intended effect. By the end of the role play, students were able to see that no Aboriginal peoples remained in their original place.

Types of data collected

- Teacher reflections

- Student written reflection

- Student work

- Student grades

- Minutes of teacher meetings

- Emails and informal comments

Student outcomes

Students were asked to complete a reflection on their experience of participating in the role-play. Among these responses were:

After completing this role play I felt very confronted. I felt this way as it amazes me that people actually did this

I felt sympathetic for the Indigenous people after being put in their shoes

After completing the role-paly it gave me insight into what happened in 1800-2000. It gave me more of an understanding than reading a text book. I felt sad and empathetic because of the events that took place.

I feel a lot of sympathy and empathy towards what Indigenous people had to suffer and how they are treated today. I feel this way because of the way this role-play was presented to me.

Students appreciated the opportunity to physically interact with the content, and opinions about repatriation were more informed after the role play. A physical representation of the removal of both people and objects had more impact than reading about this in a textbook.

Out of the 29 students in the class, the combined grades for the two assessment tasks were as follows:

- 6 received an A grade equivalent

- 9 received a B grade equivalent

- 9 received a C grade equivalent

- 5 received a D or E grade equivalent

[1] Aboriginal Secondary Education Transition Officer

The broader picture

Roma Mitchell’s school priorities are literacy and numeracy, and SACE completion. As well as developing a new History unit for the IB Middle Years Program, the summative tasks allowed for greater success in completion, meaning students were on track to graduate the IB Middle Years Program. The unit allowed students to develop the intercultural understanding capability as part of the SACE capabilities. The unit incorporated Indigenous perspectives into the Year 10 curriculum (ACARA Cross-Cultural Perspectives).

Year 12 Essential English

The pedagogical challenge

In her second year of the CRP project, Rachel focused on her Year 12 Stage 2 Essential English class. In this class of 22, four students were born in Australia (including two Aboriginal students) and 18 were of overseas heritage and spoke English as an additional langauge or dialect (EALD).Rachel’s challenge was teaching descriptive writing in an engaging way to a cohort who, for the most part, do not engage with reading and struggle with creative writing tasks. In an initial discussion with the students about differentwriting genres, they explained their preferences:

Analytical writing: If the text is in front of you, you don’t have to go out of the way to think of what to write

Creative writing: If it’s up to me, I don’t know if it will be right or wrong

Text production is worth 40% of the grade in Essential English, and the students had struggled with the first two creative pieces from earlier in the year.

Theoretical basis

In the context of the NewZealand education system, Kaupapa Māori researchers and educators have developed a Culturally Responsive Pedagogy of Relations. This model of CRP is based on five elements which resonated with Rachel:

power is shared

culture counts

learning is interactive and dialogic

connectedness is fundamental to relations

there is a common vision of excellence for Māori in education (Bishop et al. 2007)

Rachel also drew on Audrey B Wood’s 2016 article Along the write lines: A case study exploring activities to enable creative writing in a secondary English classroom. The author identifies a responsive classroom environment, collaboration and group work (the We-paradigm) as strategies for stimulating creativity.

Links to the ‘five key ideas’

- Diversity as an asset

- Offering high intellectual challenge

- Connecting to the life-worlds of students, and promoting life-world connections between students

- Developing quality relationships

The action research question

How can the use of collaborative mind-mapping and the ‘we-paradigm’ increase student engagement and academic achievement in a Stage 2 Essential English class?

Doing the action research

Students’ final task for the year was to produce two travel brochures and an itinerary that made use of descriptive and procedural language. The first location needed to be a famous South Australian tourist spot, and the second needed to be a location significant to the student, not necessarily a typical tourist attraction.

Rachel used several intentional pedagogical strategies:

- Incorporating opportunities for group work consistently throughout the unit

- Facilitating group work using explicit instructions, allocation of roles and use of space

- Building students’ confidence in using language by working with their peers

- Allowing students to work within their friendship groups before deciding on groups for them

- Moving from collaborating as a class > collaborating in small groups > working individually

Previously, the cohort sat in rows, and this allowed little opportunity for collaboration. In addition, Rachel suspects that her own anxieties may have inhibited peer collaboration. She was nervous to try group work with this class because of challenging behaviours and a fear that students would not engage. Would sitting closer to their peers encourage more off-task behavior?

She started the unit by changing the space, moving the tables to enable groups of three or more, but she still allowed students to sit with their friends.

Rachel used frontloading to begin the unit, gaining their interest by reading out a description she had written of an image, and having students picture the image in their heads before revealing the image. This prompted a class discussion of what did and didn’t help them picture the image accurately. This led to an explanation of the importance of descriptive words, to help the reader better imagine your vision.

To begin their first attempt at collaborative mind mapping, Rachel introduced the five senses: sight, sound, touch, taste and smell. On the whiteboard, she modelled mind mapping using the five senses about an image of an apple. Working in groups, the students then did the same for McDonald’s fries, feeding back to the class the words they came up with. Each group was then given an image (ranging from dirty shoes, a wet dog, a busy market, a basketball game and a violin). They mind-mapped the words to describe the image, without naming the image. Other groups then had to guess the image based on their description. Whether it was the mind-mapping, or the element of competition, students engaged with the activity

The focus of the next lesson was on synonyms, and using stronger synonyms in place of the generic language students had used repeatedly in previous creative writing tasks (no more beautiful, happy or sad!) This time Rachel organised students into groups of her choice, and each student was given a role (leader who was responsible for keeping the group on track, scribe, and presenter). The students practiced first as a class, using the word happy, and students suggested synonyms. Once there were about ten words, the students ranked them very noisily as a class from the weakest, least happy synonym to the strongest. This involved some debating, which is exactly what Rachel wanted.

Each group was then given a word, such as fun, see, relax and beautiful, and made a list of synonyms. Some groups used the synonyms function on their laptops, or Googled synonyms.There was a time limit ofthree minutes, after which the students ranked their synonyms from weakest to strongest. Some students were less confident with certain synonyms, which is why it was important for Rachel to deliberately group students with a mixture of literacy levels.

When asked to reflect on the process of collaborative mind-mapping, there were mixed responses:

I could share my ideas with the rest of the group and listen to their side of view

It gave different ideas and helped in using more descriptive language and other skills.

I get more ideas

It benefitted me because the more people I collaborate with it improved my ability to concentrate and work with different people

We discussed the topic and came up with more ideas

Because it helped me to form ideas and made the writing process easy.

Did not help me because I had to put up with some troublesome students

Easy to be distracted

I would rather work by myself because I get more done as an individual

It was waste of time

The class then read a number of travel articles, and watched clips from the travel show Getaway. Students created ‘word banks’ of verbs and adjectives. For every article they read, or video they watched, students identified in their groups the verbs and adjectives, adding these to their word banks. The aim of this exercise was to expand the vocabulary the students were using, similar to the study of synonyms.

Students then mapped out their two travel destinations before they began writing, adding verbs, adjectives, and the five senses alongside key words.

Types of data collected

- Teacher reflections

- Teacher observation and recordings

- Student surveys

- Student work

- Student grades

Student outcomes

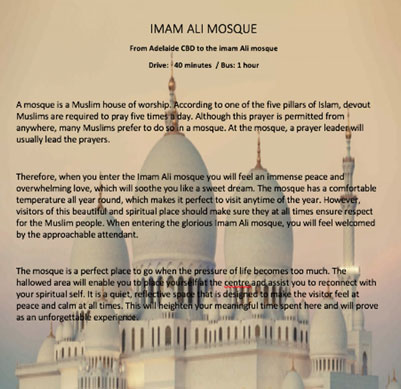

The requirement to write about a place of personal significance, but not necessarily somewhere they would normally tell others about, allowed students to express a dimension of their life-worlds, Places students chose to write about included their mosque, a temple, the local shopping centre, and a boxing club.

Students were reluctant to engage in group work at first, but eventually became used to the process, and the allocation of roles made them more accountable. When asked to reflect on the assessment task, student comments included:

I did like writing about my special place. It was nice to remember the place that is special to me. It was hard when I first arrived in Australia but this place helped me.

Yeah I really enjoyed writing about the park that is close to my heart. I enjoyed remembering the days when I first came to Australia and needed support.

I liked writing about a place that is significant to me because I can explaining the importance of the place

Yes because it allows me to comment on the significance and the importance of the place

Academic results improved since their previous creative writing task, with an increase in the number of A and B grade-band students. 100% of students said they used words from their word bank in their summative task.

The broader picture

Roma Mitchell’s school priorities include SACE completion, and this task was a requirement for completion of the Stage 2 SACE subject. The unit allowed students to develop their literacy and intercultural understanding capabilities as part of SACE. It also supported the school’s goal to increase the number of students in the B grade band. Finally, it improved engagement for both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and EALD students.

Conclusions across the two years

Experimenting with her pedagogy across the two years of action research, Rachel came to several conclusions about her evolving practice:

- Class or group discussion needs to be scaffolded. While students may understand concepts, it doesn’t mean they find it easy to ‘debate’.

- Students were willing to talk about culturally sensitive issues when they felt supported or have some prior knowledge.

- Action research supports teacher reflection and allowed Rachel to identify gaps or challenges in the curriculum, the students’ learning ,and their skills, and ro find new ways to implement change

Rachel learnt that it takes a lot of encouragement for students want to change their classroom practice and work with different peers. The process of starting with bigger groups where she could demonstrate the skill and put them at ease, then making the groups smaller was effective, as it built their confidence by the time they created their summative tasks individually.

A few of the students were less willing to participate regardless of the group they were in, and preferred to work alone, or commented that they didn’t see the benefit of formative work. The action research required Rachel to share control with what was often a complex cohort. Changing her practice so late in the course was a bit unsettling for both herself and students. By the end, many students were more supportive of each other (and Rachel, as she shared the journey of her research with them).

CRP highlights the importance of helping students make meaningful connections with their own culture and the culture of others, it builds empathy with students around different cultural groups, and makes connection with local place and space, and local histories.