Case Study:

Naomi’s STEM unit

Teacher’s name: Naomi

School: Paperbark Secondary

Learning area: STEM

Year: 9

Context

Naomi trained as a science teacher and has been teaching at Paperbark Secondary for several years. After working as an Aboriginal Education Teacher (AET), she has taken on leadership responsibilities and is currently the school’s Director of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education. Naomi’s father is Aboriginal, and in recent years she has increasingly identified as Aboriginal herself, so she describes herself as having a strong vested interest in Aboriginal education.

Paperbark Secondary has an enrolment of more than 1000 students who come from a wide range of cultural backgrounds and nationalities. Seven percent of students are from non-English speaking backgrounds and 15 percent are of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander heritage. Paperbark Secondary is located in a region that has experienced significant economic challeges due to the closure of local industries. Unemployment in this region is almost three times the state average. Apart from English (spoken at home by approximately 76% of the local population) other home languages include Hazaraghi, Mandarin, Portuguese, Romanian and Arabic.

Over the many years that Naomi has worked in Aboriginal education she has observed that Aboriginal parents want their children to receive a high quality education and the best employment opportunities. However, often due to their own schooling histories, some parents do not have the necessary skills or tools to help their children achieve the level they want for them. Naomi sees it as her job to support Aboriginal students across all aspects of schooling, including curriculum. She is keen to respond to the culture of her community.

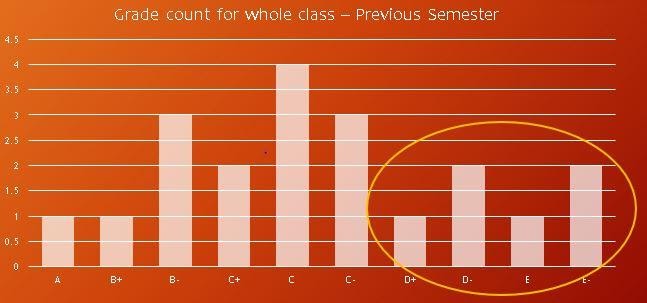

Naomi decided to focus her action research on her Year 9 STEM class. She describes this cohort as a challenging group of 23 students (14 males and 7 females) with a range of nationalities and abilities. There are 7 Aboriginal students in the class. Overall, the class is unenthusiastic about STEM and learning, and an analysis of data for the previous semester shows a group of students who had not achieved a passing grade in STEM.

Naomi was particularly concerned that five of the seven students who were not yet on track to pass were Aboriginal students.

The pedagogical challenge

Broadly speaking, Naomi’s pedagogical challenge was to engage all students, and particularly Aboriginal students, in her STEM class. Unpacking this challenge further, she asked herself:

- How am I going to engage this disengaged group of Year 9 students?

- How can I link an affinity for learning about culture with a scientific/technology based subject?

- How can I equip these students with the tools to learn about and become proficient at utilising 21st century technologies?

- How can I increase confidence in the students learning in the field of STEM?

- How can I improve my teaching practice to address the learning needs of my cohort?

Theoretical Basis

Of the several theoretical models of Culturally Responsive Pedagogy evident in the literature, Naomi was particularly interested in those models that made an explicit link to First Nations peoples.

For examle, the Assembly of Alaska Native Educators’ (1999) Guidelines for preparing culturally responsive teachers for Alaska’s schools details several teacher ‘standards’ that are intended to help Alaskan teachers to develop their culturally responsive practice. These guidelines are equally applicable in the Australian context, and include:

- Teachers understand how students learn and develop and apply that knowledge in their practice.

- Teachers teach students with respect for their individual and cultural characteristics.

- Teachers know their content area and how to teach it.

- Teachers facilitate, monitor and assess student learning

- Teachers create and maintain a learning environment in which all students are actively engaged and contributing members

- Teachers work as partners with parents, families and with the community

- Teachers participate in and contribute to the teaching profession

Another First Nations conceptual resource was Walking Together: First Nations, Métis and Inuit Perspectives in Curriculum which, like the work of Australian Aboriginal educator Tyson Yunkaporta, made use of symbolism and connection to the land as an integral component of pedagogy.

The action research question

How will providing students with opportunities to learn through observations, hands-on demonstration and cultural knowledge improve engagement in learning and therefore higher achievement in STEM?

Specifically, how does drawing analogies between past and present technologies improve learning outcomes and development of 21st century skills and capabilities for Year 9 STEM students?

Doing the action research

Naomi had been previously involved in the STEM Aboriginal Student Congress and had witnessed the impact when maths was connected to the culture of Indigenous students. Examples of this connection include the algebraic equation behind Australian Aboriginal dot painting and mathematical thinking in Navaho society. At this congress, students seemed to resonate with the idea that culture can cross over into Science, Technology Engineering and Maths concepts. Naomi wanted to nurture a similar connection in her class. In doing so, she also wanted to respond to a community of parents that had high expectations for their children and wanted opportunities for them to pursue jobs in STEM.

Naomi developed a unit of work called Sending Messages – Now and Then, in which students explored three types of communication:

- Message Sticks

- Computer coding

- Robotics

The unit began with a class discussion on all forms of communication and, later, the importance of symbols as codes in ancient and contemporary societies. Students brainstormed the use of codes, icons and symbols in their lives (e.g. emojis, road signs, language) and took turns writing and interpreting each others messages on the whiteboard. Naomi introduced the concept of the message stick as used by Australian Aboriginal peoples to aid communication between different groups and across distance. Students then designed their own codes and used woodburning tools to inscribe their own message sticks (this included a discussion of the chemistry of combustion and also risk assessment/workplace safety). During this activity, Naomi notes that the students really responded to the mentoring of Ross, one of the ASETOs at Paperbark Secondary.[1]

The unit then moved on to scratch coding which included a lot of student led teaching/learning due to different abilityl evels with the software. Students worked on their own small projects. The final part of the unit turned to robotics, and involved programming ‘Sphero’ robotic spheres.

Data collected:

- weekly reflections

- iPad photos, classroom observations by external Teacher Mentor in weeks 6 and 9

- Student survey in week 9 on their understanding of content and Naomi’s pedagogy

- Student reflections of their journey

- Student work: message sticks and scratch computer code

- Assessment plan

Student outcomes

- Overall the inclusion of Aboriginal cultural elements throughout this unit made a positive difference.

- The level of engagement for the students of concern increased and they began to express a level of curiosity and pride about concepts discussed throughout the topic.

- Only two students remained under a C grade at the end of this unit.

One student in particular was particularly responsive to this unit of work. This Aboriginal student, who had been diagnosed on the Autism spectrum, had been particularly disengaged with STEM and did not like being in a big class. He would often skip lessons. However the focus on symbols and communication drew him in and he engaged with the unit from around week 6. He ultimately produced an excellent scratch video at lightning speed.

Teacher outcomes

As a result of her participation in this project, Naomi reports the following professional learning outcomes:

- Reflecting on my own pedagogy is not as intimidating as I once thought.

- I started to enjoy listening to students ‘recommendations’ and reading student comments about myself.

- When I made modifications to my teaching that were suggested by students, it was received very well.

- My students are kinder in their criticism than I thought they would be.

- The students are very switched on and motivated when it comes to hands-on activities

- They have very valid and informed opinions when discussing historical content and social justice issues

- They often want to pursue careers in technology and need the confidence to get there

- It is fascinating to study your classroom under the microscope and pay attention to every personality and opinion more intently.

- CRP benefits students. It takes many forms and can be continually improved.

[1] ASETO: Aboriginal Secondary Education Transition Officer

The broader picture

The project intersected with several of Paperbark Secondary’s priorities including:

- Academic excellence: Increase grade point average mean score

- Improving teaching quality in order to increase student achievement

- Inproving curriculum delivery to differentiated learners through multimodal/multimedia teaching

- Enriched cultural connection for Indigenous students

Conclusions

Through participating in the CRP project, Naomi was able to look more closely at the role of culture in STEM education, and explored ways to be more culturally responsive in her own pedagogy. She used the models offered by CRP theorists to give her students the best STEM experiences she could in order to increase their confidence and affinity for the subject. She is looking forward to adapting her pedagogy to further respond to the cultures that her students bring to the classroom.