Case Study:

Janet’s EALD unit

Teacher: Janet Armitage

School: Wattle Secondary

Learning area: English as an Additional Language or Dialect (EALD)

Year level: 9

Context

Returning to teaching in South Australia in 2011 after 18 years of other roles, Janet worked in an Anangu school on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands for four years before taking a position at Wattle Secondary. At the time of the CRP project, Janet was a teacher of English and English as an Additional Language or Dialect (EALD) across years 8 to 12.

Wattle Secondary is in the western suburbs of Adelaide, an area known for several waves of immigration in the post-war period. The school has enrolments of students from more than75 heritage backgrounds and languages. Of the approximately 900 enrolments, more than 400 students are identified as having English as an additional language or dialect. The school is rated as Category 2 on the Department for Education’s Index of Disadvantage. Wattle Secondary has an enrolment of approximately 12 per cent Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander students from a variety of Aboriginal language groups across South Australia and the Northern Territory. Data metrics at Wattle Secondary usually include attendance, PAT-R, PAT-M, NAPLAN and EALD Literacy Levels. These metrics provide Janet with prior knowledge when planning for her students.

Janet decided to focus her action research on her Year 9 EALD class of 29 students from the following backgrounds: Anglo-Australian, New Zealand, Vietnam, Philippines, Aboriginal Australian, Fiji, Austria, Malaysia, Cambodia and Syria.

The pedagogical challenge

- to involve students in engaging activities in literacy and literature, while connecting the curriculum to students’ lives and affirming their cultural and linguistic identities

- diminish the ‘monolingual monolith’ and investigate alternatives

Janet’s initial interest was to develop classroom work that connects with students’ lifeworlds. In setting this challenge, she needed to design activities that help her get to know her students, their academic needs, and their cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Overlapping with her interest in socio-linguistics, Janet wanted to develop practical strategies in the classroom to honour students’ diverse cultures and languages as assets.

Theoretical Basis

Research by Ladson-Billings (1995) was a catalyst, particularly her comments about good teacher practice. Janet was also strongly influenced by Django Paris and Samy Alim’s (2014) writing about pedagogies with the term ‘asset’ (2014), which in her view goes so far to immediately dismantle ‘deficit’ ways of viewing what EALD students bring to their learning. More specifically, in relation to multilingual classrooms, Janet is enormously influenced by academic Mei French, her research in South Australia, and her workshop at the Australian Council of TESOL Associations (ACTA) in Adelaide 2018. Similarly, working with Kathleen Heugh at UniSA on projects on multilingual literacies and her articles on Functional Multilingualism are strong influences.

Links to the five key ideas

High intellectual demands

Janet used the Australian Curriculum strands as her measures of high expectations, while basing the measure of intellectual demand against research on multilingualism and cognitive neuroscience.

Connecting with student life-worlds

An essential part of the students’ task was to contact someone with whom they had a language connection. Preferably this person would be a business owner in the local community, but Janet negotiated variations on this with individuals.

Authentic publications

Students published their polished final texts to a class website on Google Sites, providing their community contact with a QR code to enable sharing. Because students were keen for their work to be of a high standard in this shared space, there was a great deal of editing and more requests than usual for assistance.

The action research question

If we nudge the monolingual monolith in the classroom what might be revealed?

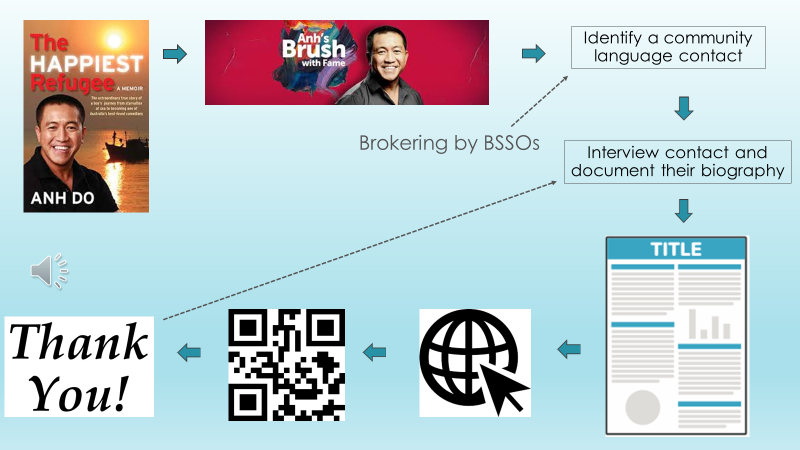

Doing the action research

The unit of work that Janet developed for the action research was based on recount, a sub-genre of narrative. First, using Anh Do’s book The Happiest Refugee, students developed their recount skills by focusing on one chapter or chapter section. They then investigated techniques of biographical interviewing through Anh Do’s television series Brush with Fame. At this point, each student identified a person in their local area with whom they had a language connection – preferably not a teacher or parent, but someone working in the community. Often, the school’s bilingual SSOs played a vital role in brokering these connections. Each student then conducted their interview, taking notes from which they constructed a text in English. Students made posters, including a recount of their interviewee and images, which were published to a website. Finally, the students wrote thank you notes to their community contact which included a QR code linked to the website, enabling them to access the posters.

Data collection included:

- in-class researcher observations, who then debriefed some moments with Janet in a casual way at the end of the observed lessons

- drafts of student writing

- polished final samples of writing on a website

- assessment data

What happened?

An immediate observed change was the use of more languages in the classroom and an increase in the interactions between students. As the project developed, students became more interested in the languages known by their classmates. As Janet and students updated the class database, students shared their experiences of receiving language support from family members, interviewing their community contact, and developing their recounts. For these EALD students, being responsible for writing someone else’s story became an important catalyst for improved writing in English.

A challenge arose when some students were not very confident in speaking their home language with people outside their family. Having a ‘language connection’ became more broadly having a ‘cultural connection’ for some students. It felt important to always see languages as assets, not as an additional way for a student to feel diminished in any way. In negotiation with Janet, two students eventually interviewed and wrote about their respective fathers, rather than a community contact.

This project brought about a positive and enjoyable shared experience in the classroom, and the optional task of sending a thank you note to their community contact was taken up by all students. These cards could be written in any chosen language, but needed to include a translation of at least one sentence from English into home language. Students helped each other or used Google translator. None of the students had previously hand written a letter, addressed an envelope, and sent it through the post, so this was a novel experience for them.

For Janet, the planning process was key to engaging students in the challenges of learning. She gave students an outline of the whole project and allowed plenty of time in lessons for questions and concerns to be expressed and resolved. Clear expectations of learning outcomes were shared, published in class documents, posted on classroom walls, and revisited regularly. Janet was explicit in the areas of the project in which she had expertise, labelling these as her domain, and did the same with areas in which the students had their own expertise. She explicitly valued student expertise in home languages and cultures and ways of connecting with community members outside of school. Knowing this would probably be the first time students had been invited to use their home languages in the classroom, Janet also allowed additional time for students’ own ideas of their project to develop and encouraged them to co-plan with each other, with their families and to check in with her often. Students co-contributed to the construction of a database of their ideas and regularly made changes and updated this with Janet.

This unit allowed Janet to trial some intentional changes in teacher behaviour in the classroom. Bringing her own multilingual knowledge into the classroom, Janet deliberately modelled ways in which language assisted her thinking and connections with others. She also asked for student assistance in correcting her spelling and usage in less familiar languages. Another deliberate action was to give permission for students to speak in any language in the classroom, except when they were explicitly practicing speaking in English.

For the first time since starting work at Wattle Secondary, Janet sought support from bilingual School Services Officers (SSO) who lent their insider information and skills in the use of languages, cultural information, and setting up connections with community members.

The broader picture

Janet’s unit of work aligned with Wattle Secondary’s strategic priorities in the following areas:

- Intercultural understanding

- Intervention and differentiation of learning

- Internationalism

- Global citizenship

- Literacy: Writing and reading

- Australian Curriculum and Cross-curriculum capabilities and perspectives

- Australian Professional Standards for Teachers

- ICT rich learning environment

Janet also carefully mapped her unit against the following strands of the Australian Curriculum:

- English: Language and literacy

- ICT

- Intercultural understanding

Conclusions

Since this unit, Janet has included space in process (formative) and product (summative) learning for home languages. Janet’s goal is to create space for multilingual learners in every class, in every unit of work, in every subject.

References

French, M (2016) Students’ multilingual resources and policy-in-action: An Australian case study. Language and Education, 30(4), pp. 298-316.

Heugh, K (2018) Multilingualism, diversity and equitable learning: Towards crossing the ‘Abyss’. In P Van Avermaet, S Slembrouck, K Van Gorp, S Sierens & K Marijns (eds), The multilingual edge of education (pp 341-367). Palgrave.

Ladson-Billings, G (1995). ‘But that’s just good teaching’!: The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory into Practice, 34(3),159–165.

Paris, D & Alim, HS (2014) What are we seeking to sustain through culturally sustaining pedagogy? A loving critique forward. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 85-100.